We weren't even out of the canyon before I had to stop to remove a couple of layers of clothing. Back on the main trail, the sun was already high, and the air was thick and warm. And so, we walked. With each rest, I examined the map and was humbled. I'd become accustomed to keeping up a three to four mile per hour pace on my walks. Wearing my home on my back, however, I was slowed down to about one and a half miles per hour, and on a good incline, of which there were many, I was resigned to an even slower pace. Jennifer, Peter, and I fell naturally into a pattern of walking on our own and meeting up now and then to rest, replenish our water supplies, and eat a little something. At Saxton Camp, we ran into the worst kind of backcountry dudes, self-styled wilderness survivalists who, upon hearing that we were aiming to summit later in the day, were happy to express their profound doubt at our ability to do so. Jennifer was right to be friendly, but I was put off. "We'll be fine," I spat, and marched away to steam, perched on the root of a huge tree. I would walk miles before I shook their bias and ill will. But leaving Saxton, I felt rested and strong. I was so excited to reach the summit, and I imagined walking back down another side of the mountain, setting up camp, and digging in to a warm supper. But until then, I walked. And walked.

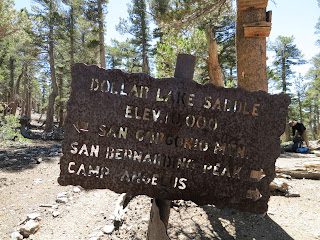

Somewhere along the way, pain crept in, and then it hunkered down. The hotspots on the backs of my heels were the least of it. My hips moaned with a dull ache. My right shoulder screamed from the weight of my pack digging into its bony curvature. But the landscape around me was lovely: silver boulders, tall pine trees and lush undergrowth, a bright blue, cloudless sky. The path rolled out clearly and dependably ahead of me, and I took every step with deliberate concentration, studying the pain as my understanding of gravity acquired a new dimension. After five or six relentlessly upward-sloping switchbacks, I was barely creeping along and wondered if I could make it to the trail junction, let alone the summit. When I finally saw Dollar Lake Saddle up ahead of me, my heart swelled with the satisfaction of arrival. I let down my pack, laid out a bandana, and tucked in to my tuna and crackers. I'd brought olives and capers to mix in with the preserved fish. The protein and salt in the briny concoction seemed to travel directly into every cell of my body. We still had three miles to walk before we would reach the summit, but we had come four and half miles and had climbed 2760 feet so far that day. I felt like a million bucks.

Out past Dry Lake View at 10,400 feet, the landscape changed dramatically. The boulders were more rounded, the trees more stunted, the shrubbery less dense. I rounded a bend, and San Gorgonio revealed itself. Bright white scree flecked with occasional low, scrubby pines and hardy alpine lichens surrounded me. The big, blue sky rose above me. Earlier in the week, NOAA had predicted a thirty percent chance of thunderstorms in the region for that day. A huge cumulus cloud billowed in the distance, but it was clearly harmless. The general all-over pain I'd been experiencing between Saxton Camp and Dollar Lake Saddle was now dominated by the blisters on my heels. I concentrated on the pain, hoping it would break up and dissolve into my body, and with one step, I felt a localized, searing pop as the left heel gave way to what was likely a nasty abrasion under the wool and leather sheath around my foot. But still, I reveled in the open sky, reveled at being in the sky and in the strange, beautiful landscape. Leaving our packs at the junction with Vivian Trail, Jennifer and I walked the last few tenths of a mile to the summit. I stepped carefully, adjusting my footfalls to minimize the pain.

At the summit camp, I was fascinated by the rock shelters. Though I'd seen them now in a few places, they never failed to charm me. Here, there were a couple of the crescent-shaped rock walls that I was familiar with, but there were also two full rings, shaped like ovals and large enough for a tent. I decided then that I would surely return on a new moon and set up camp there for a star-filled night.

The top of Mount San Gorgonio is a broad, nearly flat expanse of rubble, and the summit marker is attached to a sun-baked and snow-smoothed boulder at 11,501.6 feet, the highest point in the 60-mile San Bernardino Mountain Range, highest point in southern California. What glory I felt at being in such a place. Before me to the south: Mount San Jacinto, tallest peak in the 30-mile San Jacinto range. Before me to the west, Mount Baldy, the tallest peak in the 68-mile San Gabriels, and way off on the northeastern horizon, Mount Whitney, highest peak in the lower 48. To be here, both on the ground and so far up in the sky is a transformative thing, and I could feel the mountain working its wonders on me, opening my soul and connecting me to the universe.

Jennifer and I signed the register and wondered about Peter. He'd joked back at Dollar Lake Saddle about not bothering with the summit. At least we thought he'd been joking. We'd already been at the summit for quite a while and started to think that maybe he really didn't care and was just waiting for us back at the trail junction. I walked a few yards back down the summit path and saw him off in the distance, headed our way. We took a few more pictures and then admitted that, not only was the wind cold and hard, we were losing daylight. We remarked that the big cloud that could have been a thunderhead actually looked more like a fire, and sure enough, once we began to make our way home the next day, we learned that the Angeles National Forest had exploded with fast-moving wildfires that afternoon.

Though the sun was still relatively high in the sky, it was pushing six o'clock, and we knew that light would wane once we were under cover of the forest, down below tree line again. Peter admonished Jennifer and I for walking too far apart now that the light was getting low, and I started to be skeptical that we would make it all the way to Halfway Camp, our permitted stop, before dark. We agreed to stay closer together and hoped that there was room for us a High Creek Camp, a good two miles closer than Halfway Camp. Rangers be damned; we were hungry and tired, and we would camp wherever there was room. Well below tree line now, the ridge lines grew dark while the treetops blazed red in the alpenglow. We trudged down what seemed like hundreds of switchbacks. I thought I heard the sound of a creek and figured that Halfway Camp must be close. I yelled up to Jennifer that I would run ahead to see if there was room. We were in luck. I dropped my pack and ran back up to Jennifer to let her and Peter know they were almost there. We quickly set up camp in the last of evening's light. After a swig or two of whiskey, Jennifer and Peter went to bed. it was close to nine o'clock, and most of the other campers were switching off their headlamps and lanterns. Thoughts of my macaroni and cheese with kielbasa still held my imagination, but when I started to set up my stove, utter fatigue washed over me. I exchanged a warm supper for a handful of almonds and a date and walnut bar, crawled into my tent, and fell asleep.

"Oh, yeah! This is a great camp! We aren't that far from the summit now. Best to be quiet; looks like there are lots of people sleeping here." Dawn patrol day hikers passed on the trail about ten feet from my tent. His companion hadn't made a peep, but still he felt compelled to warn against waking all of us campers. He woke me in the process, of course, but whatever... I got out of my tent and stared up at the moon. It was much warmer tonight. Even though we were more than a thousand feet higher here than at Dobbs Camp, High Creek was more exposed, and the sandy ground seemed to retain warmth. I lay down again and drifted off for another hour or two and then made a breakfast of tea and buckwheat granola. I replenished my water supply and broke camp as the sun crashed over the ridge, flooding our campsites with early morning glare. As I strapped on my pack, it looked like Jennifer and Peter still had a few things to take care of. I said farewell and lit out down the barely legible path.

The morning air was cool and sweet. After two days of walking with this weight on my back, I was finally starting to get it. I was able to adjust the weight to prevent or alleviate pain, and I was moving much more quickly. By this point, of course, I'd eaten most of my food, and I was carrying much less water, now that I understood how plentiful and frequent the water sources along the way were proving to be. And there was the small matter of walking downhill... But still, it felt like an accomplishment, and I grew melancholy at the thought of leaving the mountain and returning to the city. I began to catalog things I had learned so far on the trip when I lost my footing and slid a few feet down the trail. Best to wait until later to take inventory. For now, it was important to focus on just one of the the things I'd learned: walking has a form, and the maintenance of good form requires constant attention. I won't always have to pay such close attention, but I am still learning, still discovering the skill required to walk long distances. Once I obtain the skill, the attention will be inextricable from the activity. Awareness, on the other hand, will always remain discreet, separate from the skill. There is no telling what obstacles may present themselves, and awareness of one's surroundings and of every footfall can be the difference between a jaunty stroll and a total bummer. Or worse. The nice thing is, this kind of focus, repetition, and sustained attention and awareness leads to side effects like clarity of mind and levity of spirit.

As I descended the mountain, I encountered more and more people, and I could see why this trail is so popular. Every turn yields another beautiful vista. Jennifer, Peter, and I met up at Halfway Camp. We'd looked in on every camp along our route; they each had a distinct character, all lovely in their own way. As the path became more level and we crossed Vivian Creek, I figured we were almost finished with our walk. I wondered aloud about the nasty stretch of terrain we'd been warned about. Both Carrie (of Larry and Carrie back at Dobbs Camp) and a solo backpacker we chatted with at Dollar Lake Saddle told us about how awful the last stretch (or first stretch, depending on your route) of Vivian Creek Trail is, with slippery scree and rubble the whole way down its knee-busting grade. Just moments after mentioning it, I turned a corner and saw the trail fall below me. It was a shame to have such a pleasant walk interrupted by this mean-spirited hill, but we had no choice. It was awful, and all three of us came close to falling a number of times. Relieved to be "out of the woods" in more ways than one, we took a quick rest at the bottom of the hill and then bid the mountain farewell, crossing the dry riverbed and walking back through the park, busy with sundry Sunday afternoon recreating. Piling ourselves and our gear into my car, we drove the windy road back down through Forest Falls to Jennifer's and Peter's car and then back up to El Mexicano. I ate greedily, and after parting ways with Jennifer and Peter, I rolled down all of the windows and breathed deeply. As I descended the mountain, the temperature rose, and when I stopped at a gas station, it was ninety-eight degrees on the blacktop. I was happy to pass on through there but reluctant to let go of the mountain.

Go to Part I

No comments:

Post a Comment